Table of contents

- Deep roots: the beginnings of bento in ancient Japan

- The Momoyama era (1573-1603): the beginnings of elegance

- The Edo period (1603-1868): democratization and diversity

- The Meiji era (1868-1912) and the arrival of the railroads

- The 20th century: between domestic tradition and industrialization

- Today: between tradition, healthy living and minimalism

- Which dishes to prepare for your bento?

From deep roots: the beginnings of bento in ancient Japan

The word bento" (弁当) literally means "something practical" or "ready to go". Although the term was only widely popularized from the Edo period (1603-1868) onwards, the origins of the bento as a concept and practice date back several centuries earlier, precisely to theKamakura era (1185-1333), a period marked by the emergence of samurai government and numerous social changes.

During this period, the needs of warriors, agricultural workers and travellers led to the development of transportable and sustainable food solutions. Thus was born the hoshi-ii (干し飯)white rice cooked then air-dried. This method enabled rice to be stored longer without the risk of fermentation or mold, in a Japan where refrigeration did not yet exist. To eat it, simply rehydrate it with hot or cold water.

Hoshi-ii was packaged in simple cloth bags or unlacquered wooden boxessometimes made from bamboo, and transported on long military campaigns, religious pilgrimages or outdoor work. It is thus considered the direct ancestor of the bentooriginally designed not to be beautiful, but to be practical, nutritious and easily transportable..

The samurai in particular used this type of mobile meal during their expeditions or prolonged stations in remote provinces. Similarly farmers took their dried rice along with a few pickled vegetables or a little dried fish, constituting frugal meals but sufficient to sustain intense physical work.

This early use of the bento did not yet emphasize variety or presentation: the essential thing was to be able to eat independently, without having to depend on a fixed householdin a Japan still largely rural and marked by feudal conflicts.

The Momoyama era (1573-1603): the beginnings of elegance

L'Momoyama eraThe Momoyama era Vendor a short but prolific period of decisive transition in Japanese history, both politically and artistically. This period of relative peace, following decades of civil war, saw the rise of a refined military aristocracy. refined military aristocracy who encouraged the arts, architecture and the rituals of daily life. In this context of cultural effervescence, the bento transformed from from a simple nomadic meal, it began to an object of prestige, refinement and pageantry.

It was at this time that the contents and container of the bento gained in nobility. Meals taken to hanami (cherry blossom festivals), hunting parties or tea ceremonies were no longer presented in simple canvas bags or rudimentary boxes. They were now carefully arranged in lacquer boxes, sometimes decorated with gold, mother-of-pearl inlays or plant motifs, in keeping with the refined aesthetic tastes of the time.

These multi-tiered bentocalled jubako (重箱)not only separate the dishes, but also allow you to play with shapes shapes, colors and texturescreating a veritable culinary mise en scène. Food placement is no longer left to chance: it reflects harmony, respect for the seasons and a taste for the ephemeral, values at the heart of Japanese aesthetics.

In addition, the growing influence of the tea ceremony (chanoyu)formalized by Sen no Rikyūreinforces this attention to objects, presentation and the discreet beauty of everyday gestures. The bento, when it accompanies a moment shared in the open air or a meeting of literati, becomes an extension of the art of living advocated by this culture of detail and contemplation.

In the bentos of this era, we see for the first time the idea that transported food can be beautiful, thoughtful and meaningfulno longer merely nourishing, but also revealing a social status social status, aesthetic taste and even a philosophy of life..

The Edo period (1603-1868): democratization and diversity

L'Edo perioda period of political stability under the Tokugawa shogunate, Vendor a major turning point in the history of bento. Thanks to inner peacethe growth of cities and a flourishing flourishing urban culturebento moved out of aristocratic circles and into into the daily lives of the working classesparticularly in Edo (present-day Tokyo).

The development of the arts, theater, leisure and commerce is accompanied by an unprecedented unprecedented diversification in the forms and uses of bento. It became a true cultural object, at once practical, convivial and revealing of the tastes and lifestyles of Edo society.

The makunouchi bento: the theater bento

One of the most emblematic forms of this period is the makunouchi bento (幕の内弁当), literally "intermission bento". Served during breaks in long kabukiperformances, it enabled spectators to eat while prolonging the theatrical experience. This type of bento is distinguished by its elegant and balanced composition A portion of white rice, a piece of grilled fish, simmered or pickled vegetables(tsukemono), sometimes a tamagoyaki (rolled omelette), and other seasonal garnishes.

The makunouchi bento embodies the idea of variety variety and harmony in a small spacean aesthetic that endures to this day. Such was its popularity that it became a standard in stores and catering services, inspiring even the modern industrial bentos available in combinis (convenience stores).

The Meiji era (1868-1912) and the arrival of the railroads

L'Meiji era Vendor a radical transformation of Japanese society. From 1868 onwards, Japan opened up to the West, embarked on a policy of rapid modernization, and developed large-scale industrial and transport infrastructures. It was against this backdrop of change that the railroad became a symbol of progress and a catalyst for profound changes in lifestyles... and in gastronomy.

With the construction of the first railroad lines - the very first linking Tokyo (Shimbashi) to Yokohama in 1872 - the Japanese travelled more and more frequently, whether for business, study or leisure. And with travel comes the need to eat. This is where a culinary innovation comes into play: the ekiben (駅弁), or station bento.

The first official ekiben: a simple but historic meal

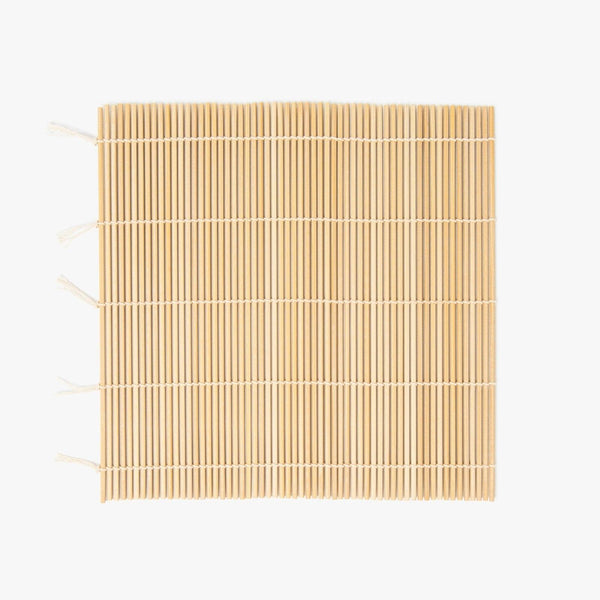

The very first first officially documented ekiben was sold in 1885 at Utsunomiya stationon the line connecting Ueno (Tokyo) to Utsunomiya. Offered by a small local vendor, this bento consisted of white rice white rice with takuan (pickled yellow radish) and umeboshi (salted plum)all packed in a woven bamboo box. Simple yet practical, nutritious and portable, this meal was the perfect answer to travelers' needs.

The idea soon spread to every region of the country. Each major station - often built in the heart of areas with strong strong gastronomic identities - began to offer their own station bentosprepared by local caterers or shopkeepers. These ekiben become regional culinary ambassadorspromoting local traditional know-how and the creativity of our chefs..

For example:

-

À Kobelocal beef is served in refined bentos.

-

À Hokkaidōthe focus is on seafood: sea urchins, salmon, crab.

-

In the Kansaiyou'll find bentos with a sweeter influence or focusing on seasonal vegetables.

The boxes themselves are evolving: from simple bamboo packaging, we are moving towards decorated wooden boxessometimes even ceramic, which become collectable collectable souvenirs. Some ekiben are designed as veritable miniature cultural experiencescombining aesthetics, terroir and practicality.

More than just a meal: a symbol of regional pride

The ekiben is more than just a much more than a travel snack. It becomes :

-

a symbol of local identity,

-

a tourism promotion tool,

-

and an expected pleasure of the train journey.

Buying an ekiben before boarding, or during a short stop, has been an integral part of the Japanese rail experience since the Meiji era.

The 20th century: between domestic tradition and industrialization

Over the course of the 20th century, particularly after the Second World War, the bento took on an intimate, family dimension, becoming an integral part of everyday Japanese household life. It became the meal that people carefully prepared for themselves or their loved ones, often in the morning, before starting the day. Much more than a simple culinary preparation, this gesture is perceived as precious attention, a Vendor affection and devotion, in the image of simmered evening dishes.

The boom in school and work bentos

In schools, the bento is gradually replacing school lunches. At lunchtime, children open their little boxes, often decorated with the effigy of their favorite characters, and discover the contents, meticulously prepared at home: rice dumplings, Japanese omelettes, tempura vegetables, sausages cut into octopus shapes...

For adults, the bento also accompanies professional life. Taken to the office or bought on the way, it becomes a central central element of the lunch break in a rapidly urbanizing Japan. The rise of "salarymen" and female students is reinforcing the need for practical, transportable and quick-to-consume meals.

Industrialization: bento, konbini and modern society

In the 1960s-1970stwo technological innovations radically changed the food landscape:

-

the emergence of plasticThis made it possible to mass-produce solid, lightweight, washable and inexpensive food cans;

-

the the widespread use of microwave ovenswhich makes it easier to reheat ready-made meals quickly.

In the 1980s bento reinvented itself with the kyaraben (character bento) phenomenon, in which food is arranged in the shape of characters, animals or manga figures. This trend arose from the desire of Japanese mothers to make meals more attractive for their children, while ensuring a balanced meal. The bento thus became a means of artistic expression and a symbol of kawaii cultureculture, associated with all that is "cute" and "adorable".

Bento picks - Torune - 4.50 € - bento garnish

Onigiri bento picks - Torune - € 4.50

Today: between tradition, healthy living and minimalism

The bento continues to reflect essential Japanese values: care, balance, seasonality, aesthetics and the fight against food waste. Today, it's adapted to modern consumer expectations.

Ecological: a return to sustainable materials

Bento favours wooden boxes wooden, bamboo and stainless steelreducing the use of disposable plastics. This return to natural materials helps preserve flavors and respect the environment.

Beige bento lunch box 600ml - Ippinsha - € 38.00

Health: lighter and more varied

Modern bentos include more vegetables vegetablesand lean proteinsand vegetarian options or gluten-freefor healthier, more balanced dietary needs.

Global inspiration: the international bento

The bento concept has seduced cities around the world, from New York to Parisinfluencing modern lunchboxes. It embodies both convenience, aesthetic and culinary diversitybecoming a global phenomenon.

In this way, the bento adapts to contemporary challenges while preserving its culinary heritage.

Lunch bento at BIWAN - the table

Which dishes to prepare for your bento?

The secret of a good bento is the balance between flavor, texture and practicality. It's not just about filling a box, it's about putting together a complete meal that's pretty to look at, easy to eat... and stays tasty even at room temperature.

Here are a few ideas for small Japanese dishes perfect for garnishing a bento:

-

Korokke (potato croquettes): crispy on the outside, melt-in-the-mouth on the inside, they're easy to eat cold or at room temperature.

-

Tamagoyaki The sweet and savoury Japanese omelette, soft and rolled up, a sure bet for every bento!

-

Chicken karaage Marinated and fried chicken, juicy and crispy, very popular with children and adults alike.

-

Rice with umeboshi: rice is the basic ingredient, but you can twist it with a salted plum (umeboshi), sesame seeds or a little furikake.

-

Pickled vegetables (tsukemono) For a tangy, refreshing touch that balances fried dishes.

-

Mini teriyaki dumplings: easy to prepare in advance, they fit perfectly into the corner of your bento.

-

Cold salads (goma-ae, kinpira) Cold salads: green beans with sesame, carrots sautéed in soy... simple but delicious side dishes.